There are many ways to close a dark portal, but only one way to create one.

To craft a portal, you’d need to have a few ingredients. Moonlight. Dragon scales. Unicorn mane. Something owned by your great-great grandparents, and a blade that had lasted ten years without ever cutting so much as a piece of paper. Some writing whose author had been forgotten, and one precious memory that you were willing to sacrifice to the cause.

Once cast, a portal was roughly a meter wide, and perfectly circular. It had a sort of purple shimmer on the edges, and in the center, it was a black so deep and so dark that it seemed to suck the very light out of the world around you. Some records reported hearing strange sounds from the dark portal, and others reported seeing strange creatures. Eyewitness reports, though, were hard to come by, and usually incomplete. Most people who got close enough to a portal to write one up died in the process.

Create Portal wasn’t really a difficult spell; but it was involved, and time-consuming, and the general consensus between scholars, magicians, and government officials was that it wasn’t likely to be used by any magician worth their salt.

“It’s a finnicky process, and it’s just as likely to kill you as anything. Seriously,” Professor Amiratus said, clacking his teeth in a skeletal chuckle, and fluttering his phalanges in a dismissive gesture over his half-eaten food. “Whoever would bother with something like that? If you want to get in contact with another realm of consciousness—summon a kitten, or something.”

He chuckled at his own joke, and glanced nervously between the two heavily armored royal guards. His hope that they had barged into his office and interrupted his lunch in order to question him about dark portals out of simple scholarly interest was swiftly diminishing. From their dark expressions, this was serious.

Amiratus hated it when things were serious. Especially when they decided to be serious right in front of his sandwich. His lettuce was wilting, and so were his spirits.

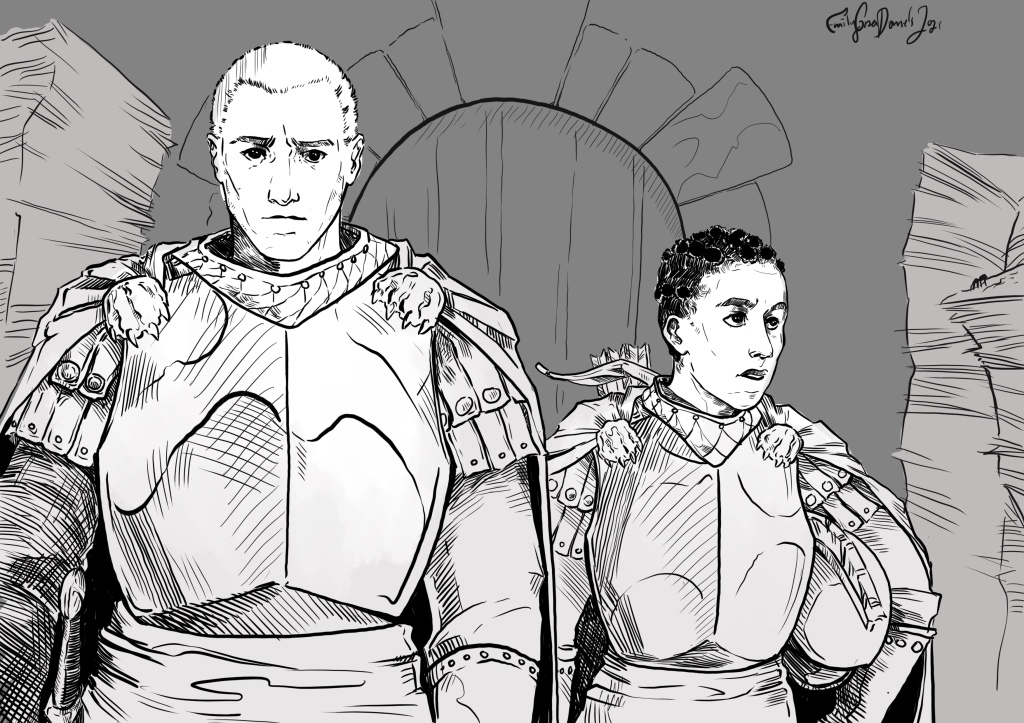

“Apparently, Professor, someone decided to,” the taller, more attentive of the two guardsmen said. His name was Grellig, and he had a face that was nearly as stoic as his helmet. His partner, who had introduced herself as Zell, was eying the stacks of ungraded papers that lined the walls of Amiratus’s office with trepidation, evidently expected them to topple over on her. “Since you’ve been recognized as the kingdom’s foremost expert on magical portals, due to your—”

He gestured, perhaps somewhat insensitively, to Amiratus’s figure. Amiratus looked down at his bare ribcage. In the first few weeks after his accident, he’d tried to continue clothing himself; but, as it turned out, it was rather hard to find a tailor experienced in finding a flattering cut for a skeleton.

That had been a long time ago. Amiratus had since found the use in using his forbidding figure to warn new students about proper lab safety. He was comfortable with his current form, odd though it was. That didn’t mean he liked it being gestured to, mid-conversation, as if it was something he might have overlooked.

“Due to my traumatic experience that I, alone, out of the half-dozen magicians around me, survived?” Amiratus asked, keeping his tone light. “The deeply tragic event of which I have no memory, that quite literally stripped all the flesh from my bones? Is that what you’re referring to?”

“Yes, sir. That.”

The guard didn’t even have the good grace to look abashed. Zell seemed not to have heard any bit of the conversation, staring transfixed at the sample jar of living eyes on Amiratus’s desk. The eyes, curious, spun around to stare at her in return. She startled, taking a step back, perilously close to one of the stacks of papers.

“Please don’t knock over my tower of procrastination,” Amiratus said, holding out a hand. “It’s scrupulously organized.”

“It…is?” she asked. There was enough doubt in her voice to frazzle the talents of every circus psychic in a twenty-mile radius. If Amiratus still had eyebrows, he would have raised one.

He didn’t, though. Very inconvenient, that was.

“Youths in my day treated their elders with more respect,” he griped, getting up from his desk and opening a drawer. He picked up the jar of living eyeballs and put it away, shutting the drawer. Too much exposure to light shortened their lifespan significantly. “And yes, my whole office is scrupulously organized. If that stack of papers wasn’t where it is, it would be impossible to walk through here.”

She frowned, but didn’t try to contradict him. Amiratus had been rather hoping she would. Pointless arguments were one of his few remaining joys in life.

“I assume this means you’ll come with us, sir?” Grellig asked.

“No, I just heard that the kingdom was in danger from a mysterious dark portal, and I decided that this would be the perfect time to take a walk in the park.”

He shuffled through the mess on his desk, scaring several spiders.

“Sorry, dears,” he said, as the spiders scuttled to find new hiding places. “Just looking for—this!”

He pulled free a dusty leather satchel, unseating a stack of papers in the process and sending them in a fluttering drift to the floor. He spared a glance for the mess, then pulled the satchel open and opened one of the drawers, frowning down at the array of magical ingredients. There were many spells to choose from in closing a dark portal, but only one that would work on such short notice, and that one needed some ingredients that wouldn’t fit in Amiratus’s desk drawers.

Amiratus stuffed a pair of scaling circlets into the bag, as well as a small pouch of powdered oak root, and a vial of medical alcohol. He really hoped he wasn’t forgetting anything.

“We’re going to need a goat,” he muttered, half to himself. Something glinted slightly from inside the bag, clinking against the clay vial of alcohol, and he frowned, pulling it out.

It was a small, silver tin, a gift from one of his students. A gift shop purchase, full of cards inscribed with simple spells meant to entertain children, but richly made. It had been a kind, if useless, gift.

“Is that all you need?” Zell asked, at the same time that her partner said,

“A goat?”

“Yes,” Amiratus, tossing the little tin back in the bag. “A goat.”

—

Grellig didn’t like venturing into the university on the best of days. In fact, he very much enjoyed leaving the place. It was a microcosm of reality, with so much influence over the outside world, and yet so little connection to it. It made his head itch.

Grellig paused, briefly, as they left the gate. He usually did—just to take a moment, and savor the smell of sanity in the air. Zell stopped beside him, taking the time to put her helmet back on her head.

The small, angry skeleton man charged on ahead of them both. Somehow, he had donned a robe on their trek down from the literal ivory tower his office had been in. It was purple. What little sunlight was shining past the pale clouds made the embroidered constellations on the robe sparkle slightly.

Grellig sighed, and Zell gave him a look of sympathy. No sanity today, then. He probably should have expected that.

“Onward,” Professor Amiratus declared, “To the goat!”

Grellig sighed even deeper, and began to trudge after Amiratus. The animal market was in the opposite direction, but it seemed wise to let Amiratus figure that out on his own. Scholars were rarely either friendly or helpful if you happened to embarrass them.

He didn’t think to relay that advice to Zell. Before he could say anything, the woman jogged forward, her wooden crossbow clanking obnoxiously on her cuirass. Amiratus turned at the sound, steps slowing.

“Goats are that way, sir,” she said, jabbing her thumb in the opposite direction than the one they were traveling in. “Most of the market, too.”

“It is?” Amiratus asked, tipping his head to one side. “That’s odd. It used to be—” he paused. “Oh, but of course. That was before the Kavax invasion, wasn’t it? It’s been rebuilt since then.”

The Kavax invasion had happened over seventy years ago. Not even Grellig’s grandmother remembered it.

Amiratus spun on his heel, and made an expansive gesture with one skeletal hand.

“Lead the way, then! I’m bound to get us hopelessly lost.”

Well. That was easier than Grellig had expected it to be.

“What do we need a goat for, sir?” he asked. He had an uncomfortable feeling that the answer was going to involve stone tables, knapped-flint knives, and blood. His family had raised goats. He liked them, and while he wasn’t above cooking up some goat stew every once in a while, he liked them best when they were alive.

Amiratus snapped his bedazzled cloak, gathering it close to his ribcage with a theatrical gesture, and declared,

“You’ll see soon enough.”

Grellig, not at all reassured, grimaced.

—

They made it out of the market just as the first vendors were beginning to shut up their shops, and out of the city just as the sky was growing purple with night. Amiratus thought they had made fairly good time. Judging by the scowl on Grellig’s face, though, the guard did not agree. The big man looked down at his armful of goat with an expression most people reserved for their most despised enemy, or cups or tea that had gone prematurely cold. He dumped the armful off on Zell, who scrambled to keep the bleating creature from kicking its way free of her hold.

“How far away is this portal, anyway?” Amiratus asked.

“Not far at all,” Zell panted, grabbing the goat’s leg mid-leap and hauling it back into her arms. “Some of the king’s rangers discovered it in the royal forests this morning.”

“Royal forests,” Amiratus snorted, and even out of the corner of his eye socket, he caught the way that Grellig bristled at his tone.

“What’s the matter, royal guardsman?” he asked.

“You’re coming close to insulting our King,” Grellig growled. “Men have been exiled for less.”

“They have!” Amiratus said cheerily. “That’s part of the problem, really. In my day, kings were a great deal humbler. They didn’t claim ownership over forests, and rivers, and roads, dear heavens. Nowadays, they seem to sit about in their royal robes and expect the world to hand them adulation and material wealth on a golden platter. And what do they give in return, I ask you?”

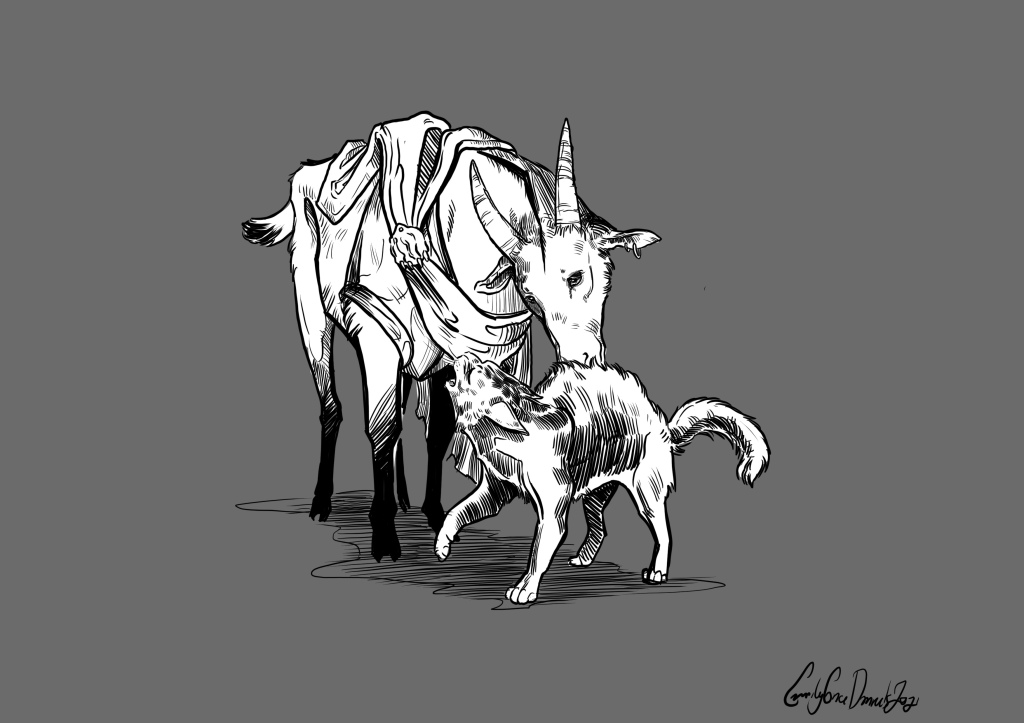

“Hasn’t the king always owned the forest?” Zell asked. She seemed to have succeeded in calming down the goat in her arms—a truly impressive feat, if Amiratus’s knowledge of the nature of goats hadn’t become as horribly outdated as the rest of him—and was occupying herself by gently scritching at the creature’s nubbin horns. The goat was butting her hand affectionately. It was deeply adorable.

“Yes,” Grellig growled, at exactly the same time that Amiratus said,

“Of course not!”

Grellig glared at him. Amiratus couldn’t glare anymore, but he’d heard that some people found looking him in the empty sockets rather discomfiting. He hoped that Grellig was discomfited.

“It was during the reign of our first queen,” Amiratus said. “Two barons brought a complaint over land ownership to her, in an attempt to claim that she’d show unfair favoritism. She was too clever for them, and ended up convincing them both that all land not currently being used for building or agricultural pursuits belonged, by default, to her. The crown has held onto that land ever since–thus, royal forests.”

“Huh,” Zell said, sounding contemplative. Not for the first time, Amiratus wondered how much of the land’s history was actually taught to those who occupied it. Probably not much. It was hard to be proud of a nation when you knew how many petty feuds had shaped it.

Grellig seemed to have let Amiratus’s little history lesson fly in one ear and out the other. He was tromping on ahead, armor clanking, making use of the longer legs that nature had blessed him with.

“It’s getting dark,” he growled. “We should have left sooner.”

“If we’d left sooner, we wouldn’t have had our goat, which we needed to close the portal.” Amiratus said. “As for the dark—let me help with that.”

He snapped his fingers, and a glowing white orb fizzed to life above the three of them.

To be entirely fair, he cast the spell at least partially out of annoyance. He knew it might startle the two guards. A little harmless prank. He wanted to see Grellig jump.

Grellig didn’t jump.

The goat, however, did.

With a startled bleat, it kicked its way free of Zell’s arms, nothing but a small black-and-grey blur, disappearing into the underbrush. Amiratus didn’t even have time to curse himself for an idiot.

“Aak! Follow that goat!” he shouted. At the orb, mind you. The ball of light was a simple, obedient bit of magic, one that should be visible from a long way off.

But, of course—of course, the two guards thought he was shouting at them. They were far too used to following orders, too. Anyone else might have paused, said something like ‘Are you sure?’ or ‘Maybe we should consider other options’ or even ‘Of course I’m not going to plunge blindly into the forest, that’s insane, and so are you.’

But they didn’t say any of those things. Even Grellig didn’t so much as hesitate to dive headlong into the underbrush. Amiratus, unwilling as he was to be left behind, had to rush after them.

“Stop!” he shouted, but either the two couldn’t hear him over the cacophony of clanking armor and crunching leaves, or they thought he was yelling at the goat. “Slow down!” he tried, as he fell further behind them both. How did they run so fast with all that armor on?

As goat, guards, and orb all alike outpaced him, it became more and more difficult for Amiratus to see. Long, whippy thorns grabbed at his legs, and it wasn’t long before he cracked his shin on a soggy old tree trunk. The jolt was hard enough to send his loosely-held-together bones flying in all directions.

The clatter of armor and the crashing sound of trampled flora moved further and further away. The light of Amiratus’s orb bobbed along, just visible through the tangled mess of branches and leaves.

Amiratus groaned softly from where his skull had landed underneath a fern.

Over the course of the years, he’d discovered that whatever the experience of going through the dark portal the first time had done to him had permanently bound his consciousness to his bones, his skull in particular. It was his own spellwork, however, that bound his bones to one another and made them ambulatory. It had been shoddily done—he was not too proud to admit that, if only to himself. If he’d ever bothered to renew the spells with the greater wizardly knowledge he’d accumulated over the years, he’d have been able to do something really useful—for example, say a single word and have his skeleton reassemble itself on the spot.

But he had never done that. He’d been putting it off.

With a groan, he willed his arm to move, pulling itself along like a drunken inchworm and feeling along the mossy ground for his other bones.

As he found missing pieces and put them in close proximity, the spellwork snapped them together like magnets. His legs and his arms were still separate from one another, ambling about drunkenly. From where his skull lay, He thought he could see his ribcage, large and white against the darkening forest, and he sent his reassembling selves after it.

This would have been easier with a light, but the orb spell couldn’t be cast and held more than once. If he cast it again now, Zell and Grellig would be left in the dark—literally. They’d probably be lost, and the goat would definitely be gone, and then they’d have to start the entire portal-closing procedure over again tomorrow.

No, it wasn’t worth it. Assembling himself in the dark it was, then.

The bobbing light grew ever more distant. By the time Amiratus had finally found his left thumb phalange, it was barely a speck in the distance.

“Don’t wait up,” Amiratus griped. “Don’t mind me at all. I’m just the only wizard who could possibly know the spell to close the portal, after all. That’s definitely not important.”

His thumb clicked into place, and Amiratus gave it an experimental wiggle. He seemed to be more or less in order. He couldn’t sense any missing bones, anyway, and that was about as good as he thought he was going to get in the dark.

A scream pierced the night, stabbing like a needle, and tugging the thread of his attention to the bobbing light in the far distance.

The light of the orb blinked out, leaving silence in its wake.

—

Grellig felt himself falling. It was a strange feeling, like the jerk of sudden terror that usually jarred him out of a bad dream—mortal fear surrounded by utter silence, utter lack of sensation.

But he wasn’t waking up.

He blinked, in hopes of making his surroundings clearer. Instead, it seemed that the blurred, rippling lines were as close to well-defined as they were going to get.

“Zell,” Grellig shouted. His voice seemed to waver, though he wasn’t afraid. He wasn’t. There wasn’t anything to be afraid of yet. For all he knew, he was simply asleep! Ha. Probably dreaming. He’d wake up any moment now.

His voice did not echo in the emptiness. Instead, it seemed to be absorbed into the soft, rippling—cloth? Mist? It was impossible to tell what it was that surrounded him. The very center of Grellig’s chest felt sunken and raw, the feeling of falling sticking with him.

“Zell!” he shouted again. They’d been chasing that accursed goat, and Amiratus’s light had been bright enough to blind them both. She’d dove in after the animal, and Grellig had barely had enough time to register that they’d both disappeared, just barely noticed the glowing ring of purple light. He’d tried to stop, but he’d fallen in anyway.

They’d found the dark portal. They were inside it. Which meant, hopefully, that Zell was around here somewhere.

Again, though, his cry was absorbed into the strangely rippling dark. It was like being smothered by richly dyed velvet. The warm, soft numbness that was beginning to seep into his limbs was almost pleasant—or would have been, if Grellig’s terror hadn’t been filling his lungs with the need to move. He began to struggle. Somewhat pointlessly, as it turned out, because the soft, almost wispy material that seemed to make up the inside of the portal only gave way to his struggles, leaving him as helpless as a deer on ice.

Something shifted in the murky depths. A dark shadow, larger than any creature Grellig had ever seen, moved behind the curtain of mist, and its moving made a strange sound, like a heaving breath or the scraping of stone upon stone. Grellig could not move in this reality, could barely comprehend it, but the shadow that lived in the shadows could. Grellig felt the fear of finding himself in enemy territory, compounded tenfold; at least in the conflicts he was used to, enemy territory rarely rendered him this utterly helpless.

The moving thing moved again, and Grellig tried to strain backwards as the mist began to part, and a great head broke through, black as night and shining like a sapphire. A pair of glowing orange eyes looked down at him, and a voice spoke, in a hollow, echoing boom,

“What is this?”

“It’s—I’m—me,” Grellig said the first thing that came to mind. It seemed awfully breezy, all of a sudden. A cool wind brushed against his temples and buffeted his ears.

The face—the giant, strange, inhuman face—gave a very human frown.

“I’m sorry, what?”

“I’m me!” Grellig shouted, somewhat idiotically, against the suddenly overwhelming wind. It seemed lighter all of a sudden. He was casting a shadow, he realized, on the strange material of the inside of the portal.

“You can speak?” the face asked, sounding surprised.

“Of course I can—”

The wind, which was uproarious now, catapulted something out of the darkness at him, hitting him directly in the face. Grellig coughed, spitting out a mouthful of fur, and frowned down at the thing in his arms.

The goat bleated back.

Grellig barely had time to be perplexed, before the wind tore the animal out of his grip, sending it catapulting into the bright circle of light behind him.

The bright circle of light that he was fairly certain hadn’t been there a moment ago.

“What the—what was that,” the face demanded.

“Our goat.” Grellig explained, helpfully, second before he had the sudden thought that maybe the face-creature was asking about the expanding, light-filled hole in the middle of their dark portal realm. He didn’t have time to double back and explain, though; because the next moment, he felt something hard and cold wrap tightly around his ankle. It jerked him towards the light, and the wind helped it along, until between the two, he was nearly flying. He had enough time, just, to see the clawed hand as it reached out to grab him; but he was moving too fast for it, now. He shot out of its grip just as the claws clacked shut over empty space. There was a blazing light, a sound like tearing cloth, and suddenly, he was lying on his back on cold, wet earth, misty night air filling his lungs. After the otherworldly numbness that had surrounded him inside the portal, the sudden rush of sensation bordered on painful. Still, it was a relief. He heaved deep breath after deep breath, all but drinking the air.

“Are you all right?”

A skull appeared in Grellig’s vision, skeletal fingers brushing up against his throat, checking for a pulse, and then beginning to prod his ribs. The professor wasn’t wearing his cloak anymore. Small mercies.

“Still alive, good. Still have all your bones? Do you know where you are? What’s my name?”

Grellig groaned, sitting up.

“I’ve got all my bones, Amiratus. Nothing in there hurt me. Where’s Zell?”

“I’m right here,” his partner chimed in, and Grellig turned to find her flushed, kneeling with her arms around the neck of that infernal goat, but otherwise okay. They were all in the small clearing in front of the dark portal, and Amiratus’s glowing orb was shining above them, lighting the small clearing with a blazing, eerie glow.

“Okay, so you’re all in one piece, and Zell’s all in one piece.” Amiratus said, and if Grellig didn’t know better, he would have said that the professor’s voice was almost expressing an emotion. Relief, maybe.

“And most importantly,” Amiratus said, collecting himself. “The goat’s all right.”

He shuffled over to his satchel, which had been hastily tipped over on one side, its contents scattered. Now that Grellig noticed it, he also saw the arcane lines carved deep in the dirt, still rippling blue with magical energy. The spell that had pulled them free of the portal, he realized.

“Would you mind bringing it over here, dear?”

Amiratus was shuffling through his supplies, and Grellig grimaced as he pulled free a small, ceremonial-looking dagger. Zell brought the goat over, and Grellig turned away, looking into the portal instead. It was just an animal, he thought, and the safety of the kingdom was at stake.

“There we are,” Amiratus declared, and Grellig glanced back.

The goat was still alive, munching quietly on the underbrush. Amiratus was holding something pinched tight in his fingers. A small tuft of hair.

“That’ll be perfect.”

“Hold on,” Grellig said. “You just needed its hair?”

Amiratus looked at him blankly. Not that he could really look anything other than blank, being a skeleton and all, but still. It was infuriating.

“Well, yes.” Amiratus said. “Only very dark magic uses materials harvested with bloodshed.”

“You’re telling me that all that time spent haggling over it, all the trouble of chasing it, of falling in a dark portal, and we could have just asked politely for some of its hair and been on our way?”

“Well, no,” the professor hedged. “Not really. You see, the fresher the ingredients are, the higher a chance the spell has of working properly. Seeing as this spell is largely theoretical, and the danger is so great, I wanted to—”

This all sounded like excuses to Grellig, whose blood was rushing in his ears in a way that usually preceded a fistfight.

“We could have died! I could have died, over a stupid—”

“GOAT,” The dark portal boomed.

—

Amiratus wasn’t in the best of places, right now. Geographically or mentally.

The experience of being within five feet of another dark portal, so long after his run-in with the first, was making him realize just how little he’d managed to deal with the whole ‘losing his flesh and organs’ debacle. He’d poured his past hundred or so years into the research of dark portals. He made regular jokes to his students about his new bodily appearance, and the magical mix-up that had contributed to it.

He’d thought that counted as dealing with it. But, judging by the tension and near-panic that was trembling through his very marrow, he hadn’t dealt with it after all. Not even a little.

The booming voice emanating from the portal halted the argument, which was good. He and Grellig were both just working through their nerves, anyway, and a fight at this juncture wouldn’t help anyone.

On the other hand, it was a booming voice emanating from a dark portal, and that wasn’t good at all.

“Did it just say ‘goat’?” Amiratus asked. Grellig, for some reason, looked sheepish.

“HOW DARE YOU DISTURB MY SLUMBER.”

Something pushed at the misty membrane of the portal’s center, causing it to bulge outwards. Whatever it was didn’t quite break through, and a rumbling growl of frustration shook the very ground around them.

Amiratus needed to work fast.

The ingredients he’d chosen were for for the simplest portal-closing spell he knew, and he gathered them up in shaking hands, hoping that the spell didn’t betray his confidence in it.

He dashed out the still-glowing symbols of the item recovery spell he’d used to get the royal guards out of the portal, and drew fresh magical directives in the earth after them. They began to ripple with the magical energy still left over from the previous spell.

Goat hair in the first circle, to represent the native fauna of this plane; the powdered oak root in the second, to represent the flora. He took the medical alcohol and poured it across the ingredients and into the third and final circle, which contained no ingredients, but consisted of a series of symbols articulating consumption, the reality of being crushed and demolished, absorbed into an overwhelming force. It was an unkind symbol, but a necessary one.

Using flint and stone, Amiratus lit the alcohol, combining the ingredients of all the circles into one cohesive spell, and then placed his palms flat on the ground, pouring every bit of magical energy he had into the waiting ground.

The reaction was instantanous and dramatic. The night mists gathered, and the ground trembled. Wind picked up, and leaves began to swirl around the portal. It began to shrink, crushed upon every side by a world to which it did not belong. Like the cells of the blood gathering to clot a wound or kill an infection, the pale mist coalesced into a roiling, milky substance that wrapped around the portal like an angry fist. It shrunk, making wild, jerking movements like a dying animal. Fear-driven and unwilling to lose momentum, Amiratus poured energy into the spell, ignoring the way his bones were beginning to glow, how his hands felt like they were burning where they touched the ground. He had enough magic for this spell. He would probably be bedridden for a few weeks once it was done; but he could do it. It wouldn’t kill him.

He was fully convinced of this until the portal suddenly stopped shrinking.

At first, Amiratus looked down, double-checking the spell, thinking that one of the lines had been smudged out, or that the ingredients had fizzled out. But no; all was well there. When he looked up, the magic was still working. The night mists seemed to have been angered, even, by their lack of progress, roiling furiously as they worked to close the portal, bashing against it like waves against rock, but no longer able to budge it.

It wasn’t that the spell was weakening.

No, something inside the portal was pushing back.

The ground trembled as a voice boomed, audible even over the wind.

“I WILL NOT BE ASSAULTED IN THIS MANNER, GOAT.” The otherworldly creature roared. As Amiratus watched, horrified, a set of shining claws, the color of oil-slick, burst out of the portal. They curled around the portal’s outer rim, shoving at it. Another clawed hand wrapped itself around the other side of the portal.

Amiratus redoubled the energy he was pouring into the spell, trying to fight it. For a moment, he could feel their two forces matched against one another, raw strength against raw strength. Like every arm-wrestling match he’d ever had, he knew as soon as he tried to push against this alien power that he was dismally outmatched. And, like every arm-wrestling match he’d ever had, he tried to put up a fight anyway.

The creature gave a harsh tug, and the portal tore open with a sound like thunder. It was no longer a perfect circle—its edges were sharp and ragged, and dark purple smoke bubbled out of it as the creature reached through with an arm the size of a tree trunk. Amiratus was thrown back from his spellwork, and lay groaning as the creature’s gargantuan head burst upwards, out of the portal. It was covered in snakelike scales that reflected the light in sharp, dazzling patterns like faceted obsidian, and its eyes were bright and round like an owl’s, glowing orange over its bared teeth.

“DISTURB MY SLEEP, AND YOU WILL FACE MY VENGEANCE. SHOW YOURSELF, GOAT, AND PERHAPS I SHALL BE APPEASED BY SIMPLY TEARING YOUR FLESH FROM YOUR BONES.”

I should say something, Amiratus thought. I should say something.

He didn’t say anything. He couldn’t. It was all he could do not to flee into the forest.

Because he knew that voice. He remembered that threat.

And even worse, he remembered, now, what it felt like when it was carried out.

“Hey! Flat-face!”

That was Zell, shouting. She had her crossbow off her back, a bolt nocked and ready, pointed uselessly at the creature’s face.

It turned towards her, just in time for a crossbow bolt to glance off of its tooth. It growled at her, and took a step forward, the ground shuddering under its feet.

Zell was already readying another bolt, walking swiftly backward, calm and steady in the face of danger. Grellig, too, was standing beside her, sword drawn and at the ready, as if it was of any use whatsoever.

They stood no chance of winning. None whatsoever. And yet, they stood ready to fight anyway.

Amiratus had done that once. When his flesh had still been wrapped around his bones, he’d been a young apprentice, helping a passel of older magicians in their attempt to research other planes of reality.

When the portal had actually appeared, and when the creature inside it had spoken, the other magicians had run. They’d left him alone, unprepared to face the threat, but idiotically courageous enough to try. It hadn’t saved them; they’d likely sealed their own fates, even, by turning their backs. He’d never quite managed, in the aftermath, to either excuse or condemn them for their cowardice. But now that he was faced with the same choice—run, or stay—it seemed hardly like a choice at all. He couldn’t leave the two guards to face this alone. Couldn’t, and wouldn’t.

He was surrounded by the scattered remnants of his supply pouch. He scrabbled through the mess, looking for something that might spark some idea of how to halt or weaken the creature.

His hand closed around a small tin.

He brought it up in front of his face, deeply confused for a moment, until he remembered. The pack of simple child’s trick spells. He opened it, breaking the seal on the tin, and shuffled through the cards that poured out, looking for anything that might prove useful.

“No, no,” he whispered, shuffling past spells that blew bubbles or made rude noises, losing more hope with every card.

His fingers suddenly stilled upon an unexpected find. He stared at the cheery illustration on it in shock.

Well.

That might work.

His voice trembled as he began the simple incantation. It required no ingredients, and only needed the barest spark of natural magic to set the words in motion.

The creature turned its head towards Amiratus as he spoke, and he had to stifle a heady chuckle as those familiar eyes seemed to blaze through his soul. He dropped the card, his hands still trembling slightly, and spoke the final word.

“What—” the creature began, but was unable to finish. One of its limbs seemed to disappear out from under it, and it tipped suddenly to one side. A booming protest was cut off harshly as the gargantuan beast disappeared in the smoky shadows surrounding the torn portal.

Amiratus’s portal closing spell, while put on pause, was still active. The night mists coalesced anew, and without the creature bodily holding it open, the portal began to collapse once more. The energy that Amiratus had poured out into the ground flared to life, lighting the entire clearing up in blue fire, and with a thunderous clap, the portal collapsed completely, leaving purple smoke and pale mist drifting lazily in its wake.

The night mists began to dissipate, punctuating the sudden silence by unfurling itself, and creeping out along the ground. Amiratus laid flat on the ground, feeling utterly unable to move so much as a finger.

“Professor! Are you alright?”

Zell was kneeling next to his head.

“Unngh,” Amiratus said. It was the fullest articulation of how he felt that he was able to manage at the moment.

“What did you do? Where did—where did that thing go?”

Amiratus gestured vaguely towards the dissipating mist. It was nearly gone now, and in the middle of it, where the portal had once been, stood the goat. It was nibbling on the iridescent, dark fur of a very small kitten, who was hissing at it furiously. It tried to swipe at the goat’s nose, but wobbled on unsteady legs and ended up just toppling over in its side. The goat, utterly unperturbed by the kitten’s fury, continued to lip curiously at its belly.

“Well, then.” Grellig said. “That’s impressive.”

“I am impressive.” Amiratus agreed, shutting his eyes.

“What? No. That’s not what I—” Grellig protested, but Amiratus was already dozing off, and didn’t hear the rest of the sentence.

—

“Visitors for you, professor. From the Royal Guard.”

Amiratus looked up from what he was doing, nodding at the young secretary in acknowledgment.

“Thank you, Neil. Let them in, please.”

Amiratus returned to his task, paddling his fingers lightly in the saucer of cream on the floor, and making what he hoped was an encouraging noise.

“Come on, eat,” he said. “You’ll like it, I promise.”

The kitten hiding under his desk hissed at him. It had more energy to pour into bitter fury than Amiratus had ever had in his life. He couldn’t help but admire it, honestly.

“Am!” Zell exclaimed, bursting in the door and weaving expertly through the stacks of paper to lean over his desk and wrap him in a hug. Amiratus returned the gesture, somewhat awkwardly, with his one free arm, trying to shake cream off his other hand. “I’m so glad you’re okay!”

“Hello,” he said, chuckling at her enthusiasm. “Good to see you. Is that a raincloud following behind you, or is that just the force of Grellig’s scowl?”

“If you wanted me cheery, you’d have let us meet somewhere outside of this accursed university.” The big man griped. He was holding a leash, and on the other end of it, a surprisingly well-behaved goat stood, looking around the room benignly.

“Is that a medal on Francis’ collar?” Amiratus asked, noticing the small blue ribbon.

“In recognition of acts of bravery,” Grellig said proudly. He’d grown oddly warm towards the goat after the portal incident, insisting it had contributed to their eventual success. It seemed he’d gotten the rest of the Guard as attached to it as he was.

Amiratus shook his head. “I’m surprised you haven’t gotten a little cloak and breastplate made for him yet,” he said, and immediately regretted it when Grellig got a thoughtful look, as if actually considering the idea.

“Well, I am sorry to disturb you.” He said. “Both of you. But I did want to hand in my report.”

It was a piece of paper among many pieces of paper, but Amiratus found it readily enough. He’d stayed up late the previous night, trying to collect his words together in a fashion that made sense. He had a great deal of sympathy, now, for his students and their late papers; but he’d managed it. He picked it up—it was folded carefully, and sealed with a droplet of clear wax.

Zell took the paper, tucking it safely away in a pouch on her belt.

“You know, they never tell us anything,” Zell said, “And I’m curious. How on earth did that child’s spell work on a creature out of a dark portal?”

Amiratus puffed his chest out a little. He was still incredibly proud of his own inductive reasoning.

“Well, It was a subject I’d been researching recently,” he said, ignoring Grellig’s prolonged groan. “Looking into the mechanics of ‘summon creature’ spells. Matter, as we know, cannot be created or destroyed; the same holds true for consciousness. So, to summon a creature, you are not creating a creature; you must, at best, be taking one from another place, and likely shape-shifting it to suit you. It was a theory, widely accepted, though not proven, that the spell stole a creature from a nearby plane of reality. I hoped, that since the creature was the nearest consciousness from another plane, that the spell would choose it. The rest was largely luck.”

He shrugged, as if it wasn’t a big deal, even though he was thrumming inside with the scholarly implications of the proven theory.

“Well, you saved our skins,” Grellig admitted. “They should be giving you a medal for that.”

“Yes, I’ll be right in line after the goat.” Amiratus said dryly. “A great honor, I’m sure.”

Grellig and Zell left, and Zell made him promise to keep in touch. As the door closed behind them, Amiratus leaned back in his chair, almost failing to notice the small black shape sitting next to his foot.

The kitten had crawled out from under his desk. It was smooshed into a tiny meatloaf shape, lapping at the dish of cream with a truly withering scowl on its face. It noticed him looking, and bared its tiny teeth to hiss at him, but the effect was ruined, a little, by the droplets of cream still clinging to its whiskers.

“I understand,” Amiratus said. “I made you a whole different shape. It takes some getting used to, doesn’t it?”

He didn’t know if either kittens or extraplanar beings had any sense of irony. He hoped they did, though.

He reached out a hand, giving the tiny thing a scritch around the ears. It began to purr, startled, and then hissed at him again, scuttling back under his desk.

“Don’t worry,” he said, leaning down. “I know what it’s like, and I’m not the vengeful type. We’ll find a way to get you home, yeah?”

The kitten hissed emphatically, and Amiratus sat back up, pulling out a blank piece of paper and a stick of charcoal to start a shopping list.“Moonlight,” he said to himself, writing slowly. “Dragon scales. Unicorn mane…”