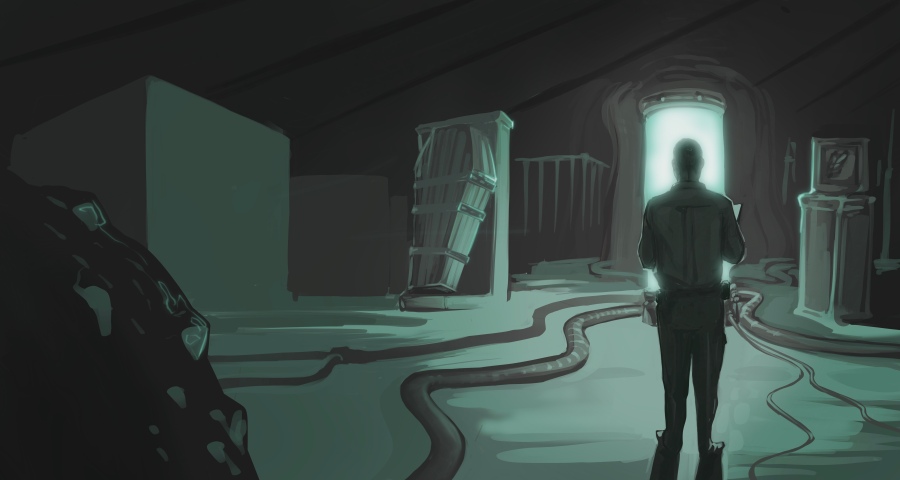

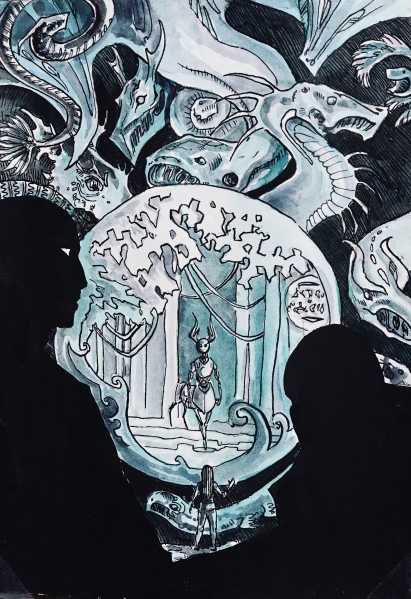

Deep in the silent warehouse, along the right side of a long aisle, between the ragged remnant of fairy wing and a coffin bound with engraved steel bands, something glowed. It spread green light over the coffin’s engravings, and shone through the fairy wing’s translucent cells. It showed up the clumps of dust on the floor, and Linh tended to use it as a reminder of when the place needed sweeping.

The tank of amniotic fluid was bolted to the floor. As he went on his rounds in the night, Linh had to take care not to trip over the lines and wires that snaked to and from the tank, refreshing the fluid inside. Like giving fresh water to cut flowers, Linh always thought. As he stopped in front of the tank, doing his best to avoid looking at the dark shape suspended inside it, Linh very carefully did not follow that metaphor further.

Instead, he focused on the glass tablet that was cradled in the crook of his arm, tapping absently at it with his stylus. On the screen, every moment of his night was spoken for. The painstaking organization of the program stood as a testament to the mind behind the rigorous cataloging of the warehouse. Next to each task, a list of subtasks, and a box to check beside each one. Linh checked off renew salt circle, and the next task on the list glowed a bright green, and gave him a button prompt. Check vitals, it said. Linh clicked the blinking button. Before the next screen came up, he lost his battle with himself, and looked up.

He saw the rhythmic cycling of vital signs appear on the tablet screen, but he barely glanced at them. The dark shape suspended in mesmerizing green captured his full attention instead.

She wasn’t human. That had been the first assurance Linh had received, as the tank had been installed and its strange contents had become part of his nightly duties. No more human than the thing in the coffin that spent the first hour of his shift pounding its fists uselessly against the dark wood, or the woman made of gray mist who drifted and wailed inside her circle of salt, or the shambling creatures kept in cages and fed once a fortnight on lumpy, pale matter. He did not ever feel the need to pause in front of those things and watch them. Then again, he never felt the overwhelming need to look away from them, either.

In the tank, she twitched. The barest flutter of her fingers, a small, jerking motion with her foot. Standing, she would have been a bit shorter than he was. A bit wider, too. Her dignity was preserved by a set of simple black swimwear, but what skin showed was rough, marked with small scars, and hairier than might be expected. Her hand moved again, fingers curling a little, as if trying to grasp something.

Linh glanced down at the tablet in his hands. Sure enough. Her heart rate was bumping upwards, steadily rising as she twitched again. Her mouth twisted, a tiny baring of teeth, and for a moment, her face did not look as deceptively human as usual.

The fit eased as quickly as it came on. Heart rate reducing, stillness overtaking her limbs. She relaxed in her tank, and Linh saw the way the light shone, throwing her ribs into sharper relief than they had been a week ago.

He moved on, checking item number 39.398 as normal.

There was a space for comments on the screen. He hesitated, half-typing a single sentence; then he shook his head. Select all > cut. The text field stared blankly back at him, but the words he could never quite commit to putting in his report drifted through his mind, not so easily deleted.

She’s dreaming.

#

Linh was convinced that work parties were an unnecessary evil.

The punch was a much higher proof than anyone warned him it would be, the rancid burn masked by excessive sugar. Linh wasn’t sure which of the two substances was giving him the headache, but his own nervousness certainly wasn’t helping. He glanced out of the office windows, looking for reassurance in the familiar layout of aisles in the warehouse below, but the glare of the overhead lights had turned the windows into mirrors, and he only saw the gaggle of his co-workers, with his own face a jarring addition to their number.

He worked the night shift, so none of them were familiar faces, except for the gate-guards. Aside from them, the only person he recognized was Ms. Cordan herself. Linh had only met the woman once, at the very last, utterly nerve-wracking, interview. The experience did nothing to prepare him for the sight of her, flushed with alcohol and chatty with sugar. It did nothing to prepare him for her being chatty with him.

Her breath smelled impossibly fresh when she spoke, in spite of the meat and cheese tray. Her crisply ironed dress laid against her skin as if arranged on a storefront mannequin, making Linh feel unusually slovenly for his clean, but slightly rumpled, shirt. She didn’t seem to care, pulling him into conversation with apparent friendliness. She gestured with her drink as she talked. The plastic cup was decorated with tiny candy canes and gingerbread men. She held it with one pinky extended, the carmine liquid inside swirling delicately as she jostled it.

“You take care of my collection more closely than most,” She said. It was about an hour before Linh usually came in to work, and an hour later than the office people usually stayed; he wondered if the strange holiday party limbo was as uncomfortable for everyone else as it was for him.

“I do,” he said, going for simplicity. And then, with some of the cowed instinct he’d had during his only other meeting with this woman, he added, “It’s quite the honor,”

“People leap at the chance to view even a single item,” Ms. Cordan agreed. And then, “But a lot of that’s just the novelty, really. It does get boring, after a while, I’m sure.”

Linh blinked. Frowned.

“Um. Yeah.”

He thought of the glass orb in aisle twelve, encased in lead and only able to be viewed through a constant camera feed; the way that even the solid foot of lead surrounding it on every side still cannot silence the clear, pure song that it sings. He thinks of the skeleton forever sleeping in its shadow box; the ribs as clear as glass and as thin as hair, the shining, preserved scales on its long tail, reflecting light like jewels.

Boring?

Unaware of his inner monologue, Ms. Cordan sighed. She looked out the window, and a small grimace crossed her face as she found the same reflection there that Linh had. Her eyes were glassy, and it was hard to guess if it was an effect of the liquor, or something else.

“I just want to see something new,” she said, plaintive. It was a strange purity of emotion to find wrapped in a silk dress.

Linh blinked. He’d been hoping to find an opening for a while now, a was that didn’t allow the black letters on their searing white background to mock him for being a fanciful fool. But now, in the not-yet-drunk haze, the unreality of being here, the both of them incongruously existing outside the easy companionship of the people who worked with one another every day. Here and now, it seemed as if the things he wanted to say…they didn’t fit in. but when nothing else fit in, they did not need to.

“I might have something new for you,” he said. His breath, coming all uneven to his lips, made the sentence stutter out in bits and spurts, and Ms. Cordan raised one perfectly manicured eyebrow at him. It was a dry, assessing, unimpressed look.

“Awfully confident, aren’t you?”

“Well, I…yes, actually, I am. Because you don’t visit the exhibits at night. Or you haven’t, since she came here, and she only dreams at night.”

She frowned, but her eyes were bright.

“Who dreams?”

#

The coffin was silent. The fairy wing was as glassy and perfect as always. And, shining her green light on both of them, curled in upon herself like a child in the womb, the woman was dreaming.

“It changes every night,” Linh said. His voice would not come out in anything but a whisper. “But she always dreams.”

As he spoke, she kicked one leg out, a small, jerking motion. The fluid sloshed in the tank, sending rippling light across the polished concrete, and in the split second of movement, Linh thought that the shape of that foot was different. Craggier. Sharper, somehow. But as she returned to the restless fetal shape, her hands tightly curled close to her face, she looked as human as ever.

“See?”

Linh turned to Ms. Cordan.

Her mouth was a flat line, not even the slightest upward quirk of life to it. She looked sad as she gazed at the tank. And then, as she saw him watching, she gave him the smallest of smiles, soft and disappointed.

“Thank you,” she said. “It does look a bit like dreaming, doesn’t it? But…I’ve seen this before. It’s just…spare electrical signals. In stasis, like this, it’s a bit like…like someone shot a gun in an empty room, and shut the door. An endless ricochet, with nowhere to land. It makes them twitch and move, just like this, but it’s nothing, really.”

She sounded so sincere, so kind. Like she was explaining that, no, the closet wasn’t full of monsters to scared child.

It would be easy to blame the punch, but the truth is that Linh has never had the best hold on his temper. There’s a reason he worked the night shift, a reason he ordered his groceries by app and always waited five minutes after the knocking stopped to pick up deliveries from his front stoop. Linh has never been the best with people, and seeing this woman deny a plain fact, right in front of his face—and have the gall to take that tone doing it?

“Is it the spare electrical signal that’s getting her heart rate up like this?” He asked, waving his tablet at her, a bit more snappishly than politeness required. “Is that what’s getting her breathing to fluctuate? Her brain activity to spike?”

Frowning, Ms. Cordan held out both hands, snapping them in midair like pincers until Linh handed the tablet to her. The glow on her face made her skin look just as eerie as the tank girl’s. She scanned the information there, the crease between her eyebrows growing deeper.

“Well, that’s odd,” she said. “Distress, maybe? That could be the sedative failing, I suppose.”

The green light on the floor danced again, the shadows shimmering in an unsettled tremor. Linh looked towards the tank to see the girl curling in on herself again. Her fingers fluttered, and he could see her pupils darting back and forth underneath her lashes. And then, as he watched, she grew still.

At first, he thought it was the settling of her dream, the way she usually fell still after the course of her dreaming ended. But instead of settling, she seemed to grow slack and loose. The look of her was less like someone asleep than it was like someone dead. And, as Linh turned back in sudden trepidation and horror towards Ms. Cordan, he saw her with one precisely extended index finger leaving the screen of the tablet. Her gaze was fixed on the tank. He could see the green reflection on the wet edges of her eyelids, the mascara making her lashes into cartoon lines around the perfect circle of her eyeball.

“There,” she said. Her voice was soft. “That. That should fix it.”

“What did you do?”

She jumped a little, looking at him like she’d forgotten he was standing there.

“Increased the sedative flow. Not that it’s any of your business. You should have made a not of this immediate—hey!”

She jumped back as he lunged for the tablet. He managed to nab a corner of it, the rubberized safety casing providing a good grip. He dug his fingers in and tugged.

She held on. Her knuckles were white as she tried to haul the tablet to herself, and Linh was jerked off balance for a moment. When he tugged in turn, she slid across the floor, concrete scraping under her heels.

It was a squabble. It was silly.

Linh had the image in his mind of the tank girl, horribly still, encased in glass like everything else in this great dead warehouse. He had a mental picture of the scaled skeleton, just a few aisles over, and the desperate, horrified suspicion that it had been acquired when flesh had still wrapped its thin, delicate bones.

In the end, he couldn’t say which of them had touched the still-lit screen, or what button they might have pressed. One moment, they were locked in a deeply undignified tussle, and the next, they both heard a sound that stopped them in their tracks.

Bong.

#

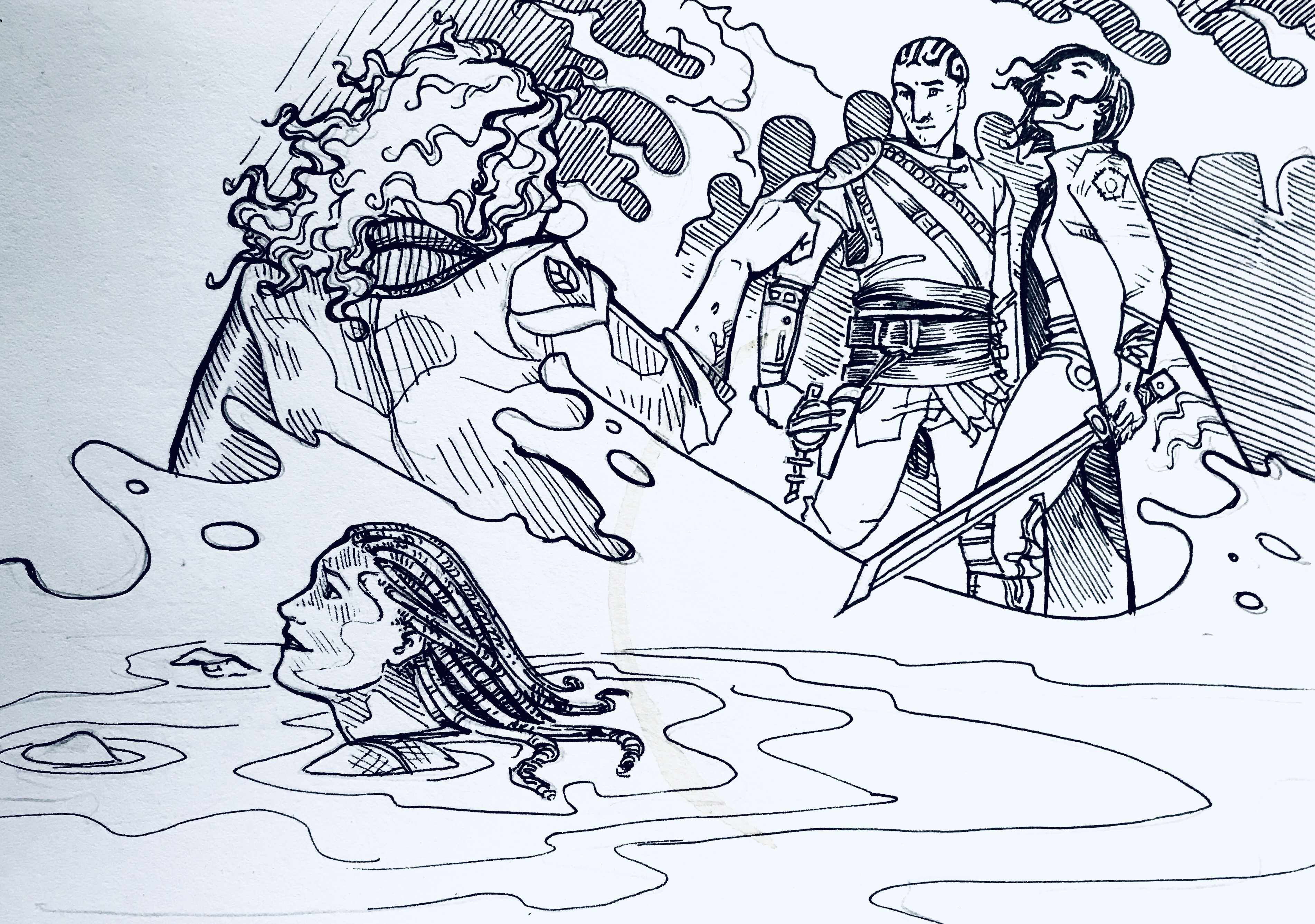

The girl’s eyes were open.

She struck the glass with an open hand, a dull, echoing sound. Her gaze was strangely focused on them both, and her irises glowed an unnatural color, warm as a flame.

Linh’s mouth was suddenly dry. He shifted, slightly, not even so much as a step; a mere shifting back and away from the tank. She caught the movement, and glared at him, that strange flame-light seeming to flicker in her eyes.

#

Linh had been to a zoo once.

It had been an enjoyably chaotic trip, himself and twenty or so other children being wrangled along from one exhibit to the next by a bedraggled group of parent volunteers and a few teachers. Most of the animals hadn’t been much interested in them, instead happy to sleep or eat or wander about their grassy enclosures as the horde of children and adults gawked at them.

At the lion exhibit, though, one of the lionesses had taken an interest. She had stalked along the thick glass, following the pack of passing children. Linh, fascinated by the rippling of living muscle under her golden coat, had stopped. Leaned in, close enough that his breath had fogged the glass. The lioness had turned in one fluid movement, bringing them face to face. Her eyes had met his. At once intent and impersonal, something about her gaze had made Linh’s neck prickle, the hairs rising. The feeling had lasted through the rest of the day, even after one of the parent volunteers had pulled him back from the glass and gotten the class moving again.

#

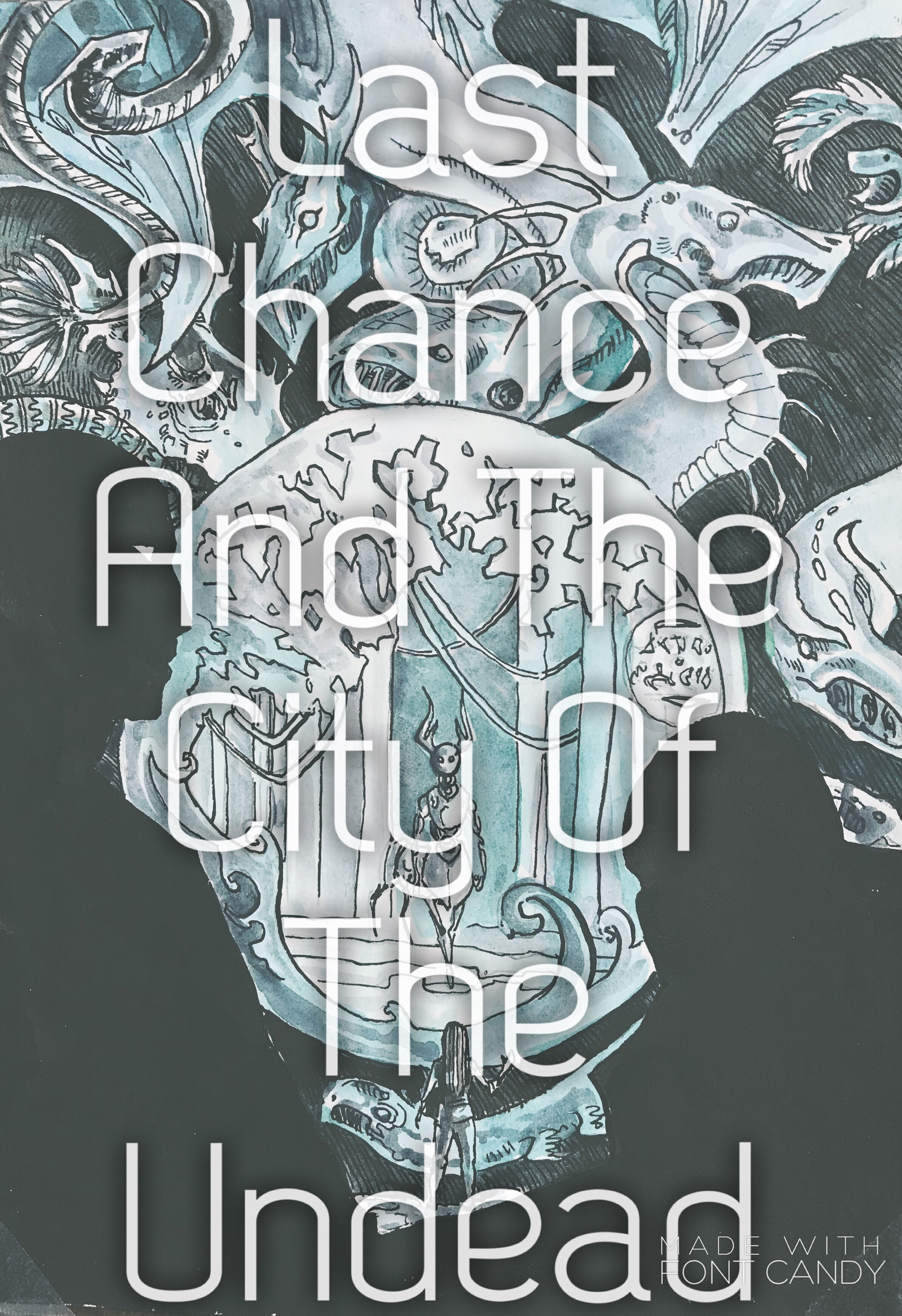

As the tank girl watched Linh, he felt the hairs rising on the back of his neck again. He barely even noted the changing of the girl’s hand until his mind stumbled over the sight of sharp claws against the glass.

Her skin, never smooth, was growing taut and rough with hair. The liquid of the tank muffled the sound of cracking and popping as her body jerked and her limbs elongated. The tablet screen was flashing panicked red messages, the warnings overlapping unread as the nodes and wires were popped from their places on her body. Even as she writhed, even as her bones cracked, her hand rammed in measured time against the glass, echoing like the ringing of the witching hour:

Bong..

Bong.

Bong.

“Oh my God, oh my God,” Ms. Cordan wheezed, panicked, as the girl in the tank lifted her inhuman, snouted head out of the dripping green ooze, as the powerful legs that no longer quite fit in the human sized tank slammed against the thick glass. Spiderweb cracks formed on the surface of the glass, creaking ominously.

The tank girl hacked like a dog, heaving green ooze onto the floor in thick, gloopy splashes. She hauled herself over the edge of the tank.

The weight was what finally shattered it.

A wave of green slime rushed out over the floor, dragging shattered glass in its wake. Fur wet, the tank girl raised her head, ears pinned back, eyes closed.

She howled.

It was a lonely, mournful sound. The only answer was an echoing shriek—the office party, which Linh had almost forgotten, only now noticing the chaos.

Flashing blue phone light caught Linh’ attention, and he whipped around, seeing the partygoers on the balcony, the towering wolf girl risen to her full height, and finally—Ms. Cordan herself, tapping desperately at her phone screen. Linh didn’t know who she was calling, and he didn’t care. The light was alerting the—the beast-thing to their location, and from the way she was growling, Linh thought that tank girl was out for blood.

“Cordan!” he shouted, and Ms. Cordan looked up, meeting his eyes for a moment. Her panicked face was perfectly lit from below by the light of her phone screen, and she just blinked as Linh gestured wildly, trying to communicate ‘put the shiny location beacon away’ by wildly pinwheeling his arms.

He’d always been bad at charades.

The beast’s fur was flattened close to her body, beginning to curl up in sharp points like scales as she dripped green goop to the floor. Growling, she turned towards Cordan. Linh could see the way Ms. Cordan’s fingers were shaking as she tried unsuccessfully to navigate her touch screen with wet hands. He could see the way the beast’s face morphed, lips curling back to reveal mottled black and pink gums. He heard her rumble a warning deep in her chest.

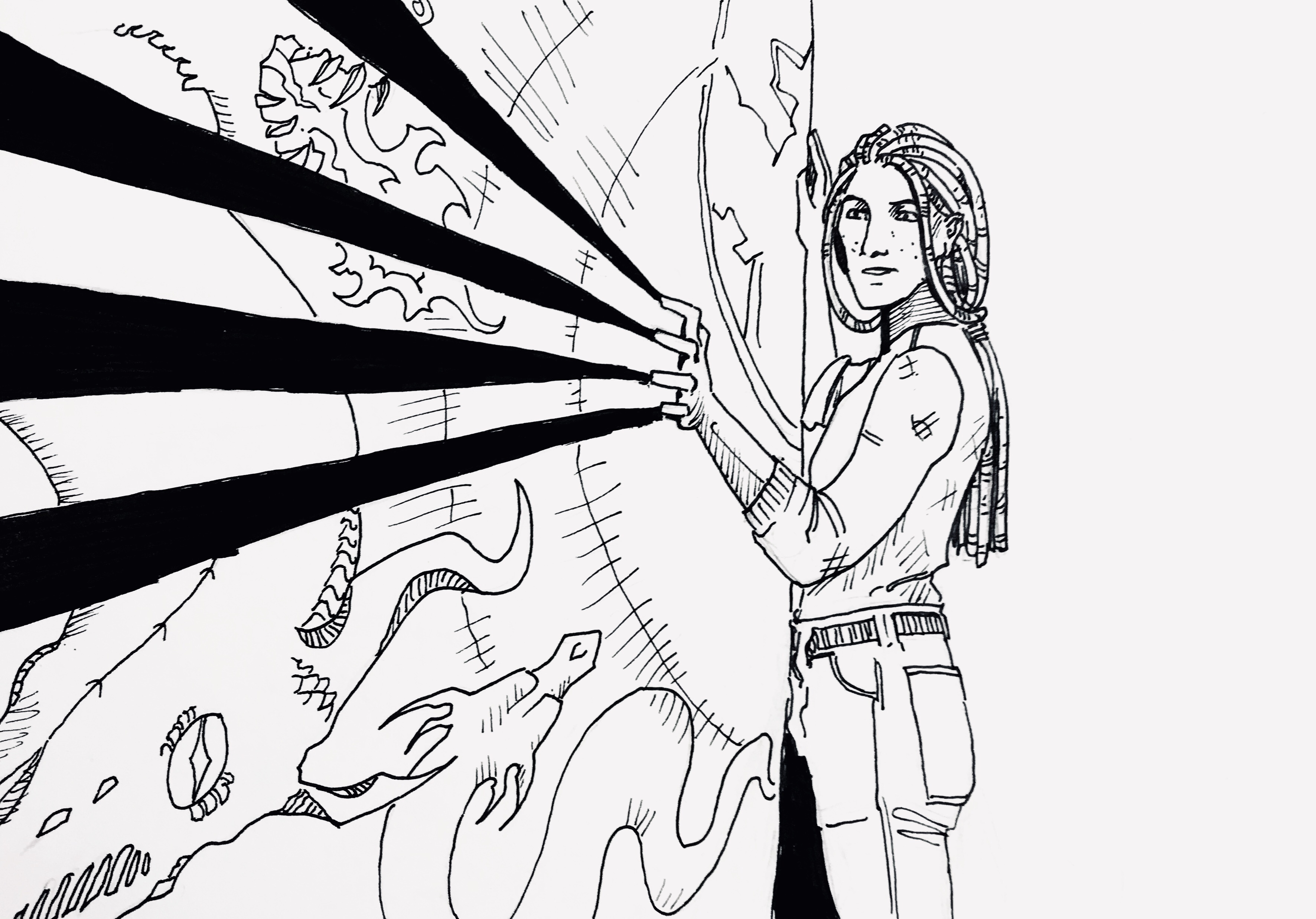

She dropped to all fours, clawed hands splaying on the floor, and leapt.

“No!” Linh shouted, as his boss was flattened to the floor under that lanky bundle of fur and muscle. He looked around for something, and found a shard of thick safety glass from the burst tank. He grabbed it. Seeing nothing but a sliver of red dress visible under the beast’s body, seeing her jaws open and slavering over Ms. Cordan’s neck, Linh uttered a courageous, slightly pitchy yell and leapt forward, driving the spike of glass into the beast’s sodden back.

It was almost exactly like stabbing through a melon rind. The sense-memory messed with Linh’s head. He stumbled back, hands shaking.

Uttering a formless, furious sound, the beast moved off of Ms. Cordan, focusing on Linh instead. Ms. Cordan was wide-eyed. Wonder of all wonders, still breathing. He couldn’t see so much as a scratch on her, no darker stain on the now-rumpled red silk.

The relief was short-lived.

The beast hit the center of his chest. His skull cracked against the polished cement floor, and he had a sudden, incongruous bout of gratitude, because he’d just swept the floor the night before, and so wouldn’t get any soggy dust clumps in his hair.

His second thought was to wonder if his skull had broken. He couldn’t feel it. He couldn’t feel any pain past the shock, only the dull sense that there would be pain, later, if he lived to feel it.

He could feel her breath, hot and foul where it hit his face. He could feel her strange hands, so much larger and rougher than a human’s; could feel the points of her dull, doglike claws where they pressed into the flesh of his shoulders. He could feel the impossible weight of her, pinning him to the floor.

Her eyes were such a perfect shade of gold. He’d walked past her every day in that tube of hers, and yet he’d never known. He’d had the gall to pity her for her protruding ribs, never knowing that the drugged sleep hid something like this.

He’d compared her gaze to the lioness’s, but that was wrong, too. She stared into his face, but also into his eyes. Something in that inhuman face searched his gaze, trying to parse his soul in the same way that he’d tried to parse hers.

Linh gulped, and fought the urge to close his eyes, to curl up, as if he could hide. A childish whimper left his lips as he scrabbled, one-handed, brushing aside broken glass, fingers searching for the corner of the tablet.

A shot echoed through the warehouse. Linh’ ears started ringing, but he felt the jolt of impact as it hit the beast. She looked up, baring her teeth, and Linh saw the bright red blood dripping through her fur. He knew his lips were moving, but if breath left his lips, he couldn’t hear his own prayers past the ringing.

His fingers slipped on the tablet screen, and he wiped them on his shirt, craning his neck to see what he was doing. In his periphery, he could see Ms. Cordan waving her arms, her mouth moving. He slapped the screen desperately, and looked up as he felt the jerking impact of another shot. The snarling beast was limping, a burst of red on her leg, but she was limping towards the gunman, not away. Linh couldn’t hear his own voice, but he felt the strain in his throat as he shouted at her. She turned.

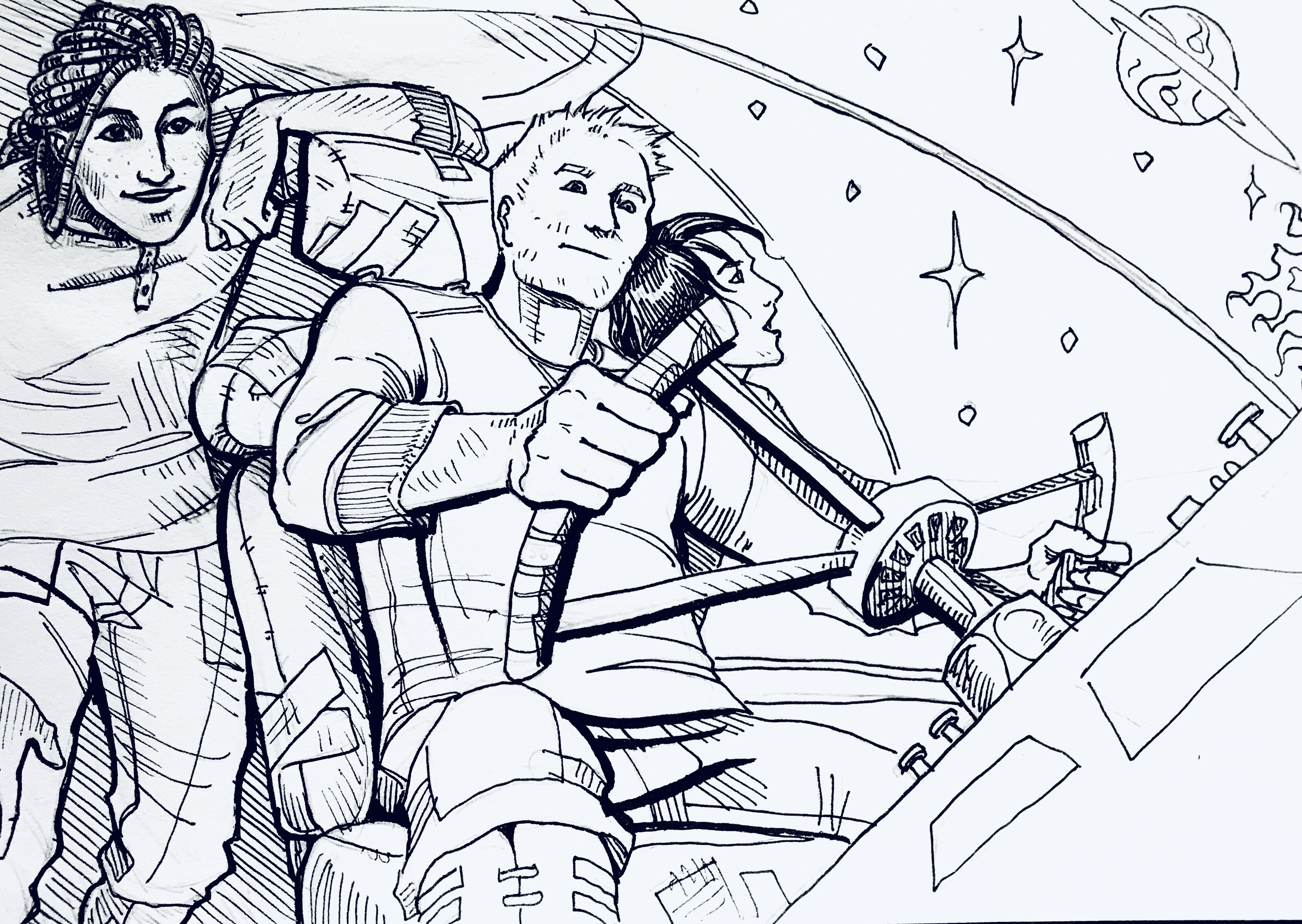

That way! He shouted, pointing towards the far end of the facility, towards the door he’d used the tablet to open. She half-turned, as if debating her chances running away against charging an armed gunman, and for a moment, Linh was pretty sure that charging the gunman was coming out on top.

And then, just barely audible to his still-ringing ears, he heard it.

Howling.

So many voices, calling as one. It was lovely as music. She twitched one ear to listen. Another shot jolted her body, but she didn’t mark it. Linh saw the red of a feathered dart in her shoulder. Not blood, then. And not having any effect, either. When she bounded towards the door, there was not so much as a break in her stride.

Linh was always going to remember the way that utter joy looked on that strange, inhuman face.

#

The doctors did their worst with casts and pins, and Linh spent a restless, drugged night being woken every two hours by concerned nurses. What sleep he got was tinged in the artificial light of the hospital room, his blinking monitor and the light filtering in from the hallway. He dreamed he was immobile, suspended in glowing green, under the curious eyes of strangers.

#

Taking sick leave was shockingly easy. The insurance, too, covered far more of the hospital stay than Linh had dared to expect.

It would have been so much easier if he’d been able to hate her.

Ms. Cordan should have been a careless employer, hellish to work for. She should have been cruel, or stupid. She should match her wealth and her business. She shouldn’t be so easy to see as a person—so easy to like.

He couldn’t afford to quit, in the end. No matter how much he wanted to. He half-hoped he’d find himself fired for freeing one of Ms. Cordan’s collection items, but the only work emails in his inbox were a sympathetic note from his immediate supervisor, and the usual biweekly copy of his pay stub.

It was stupid to hate someone for being kind.

#

The rounds were strangely calm. It felt good, having a reason to move again.

Someone was pounding their fists against the inside of the coffin. Instead of ignoring them, he reached out a hand and knocked gently on the wood.

Whatever was inside fell silent. Linh continued dust-mopping. After a moment, he heard a gentle returning knock.

Linh got his rounds done in record time so he could spend a few moments by the enclosure of the shuffling, groaning people. They devoured their evening meal with frightening alacrity, but as he waited by the bars, they huddled close to where he sat, and they seemed quieter than usual. Happier, maybe.

When he took the early bus home, he was humming the strange song of the glass cube.

#

Linh only noticed that the was collection growing smaller after the fairy wing went missing. His emails were met with assurances that the items had only been relocated, and placating thanks for noticing the issue and bringing it up.

But once he had noticed, it was impossible not to see the empty spaces. Every night, there was more floor to sweep, the collection items disappearing one by one, and never being replaced. Eventually, Linh had to bring books to work, his duties growing lighter and lighter as the collection thinned out.

He wondered if the facility was considered compromised. He wondered if he’d be allowed to work at the new one, wherever all the items were going. He tried not to wonder if whatever lived in the coffin had started up its panicked pounding again. If whomever was taking care of the zombies now would recognize their subtle signs of distress.

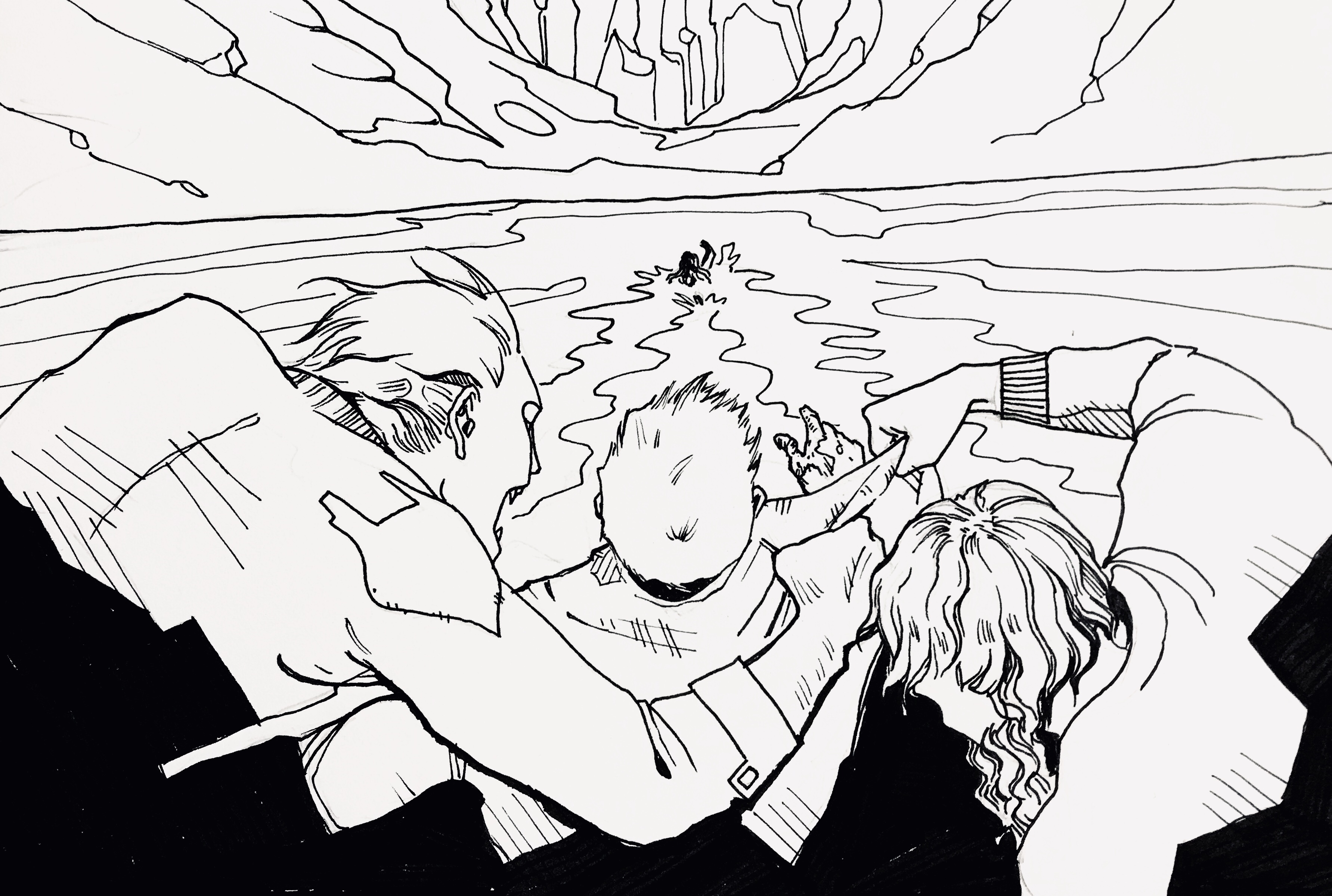

One night, the mermaid skeleton was the only thing left in the vast, immaculately clean warehouse.

Well. Almost the only thing.

Ms. Cordan was staring up into the case, her eyes moving over the iridescent scales, the eyeless sockets of the skull.

Tucking tonight’s book in his pocket, Linh walked up beside her.

“Hi.”

Her voice was quiet.

“Hi,” Linh said. He looked at the mermaid too. He’d taken to wondering what its life had been like. What its people were like.

‘are you finally gonna fire me’ didn’t seem like the right thing to say, somehow.

“I meant to thank you,” Ms. Cordan said, which was startling in and of itself. “You were right.”

“About what?”

“She was dreaming.”

She swallowed.

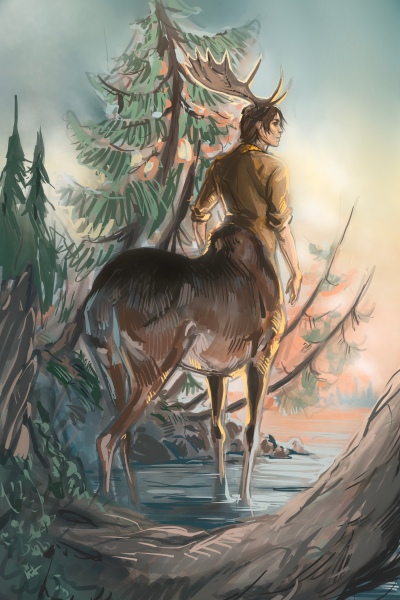

“Werewolves dream,” she said. “Vampires mourn. Fairies have a whole religion based around the bodies of their dead, did you know? Ghosts feel loneliness. Dragons can’t speak our language, but they do understand it.”

She was still staring at the case. Linh was, too. The case was a safe thing to look at.

“I returned them,” she said.

Just a whisper, but it carried in the empty building. Not quite an echo, there was no repetition of the words; it was as if they merely…lingered. Sat in all the aisles and places that the collection no longer occupied.

“Every soul, every creature, every artifact. I…” her voice tapered away.

Linh looked over the empty warehouse. He’d imagined the items being shipped away to other warehouses, to big museums or private collections.

He thought again of the werewolf. Of that soulful, strange gaze. Of the girl who looked so human, suspended in her tank, dreaming for who knew how long.

“What about this one?” He asked, nodding towards the case, and Ms. Cordan swallowed and shook her head.

“The merfolk are gone, as far as I know,” she said. “He was the last of them when I got him. I was hoping to keep him alive, to…record what I could, before he was gone. I meant it as respect. Now, I…I can’t help but wish he could have spent his last days in the ocean.”

She gave a dry chuckle.

“I’m an idiot.”

Linh thought about that for a moment.

“At least you’re a brave idiot,” he said.

She snorted a short laugh, but actually looked at him. She looked tired, her skin chapped and sun-splotched.

“You returned everything yourself,” Linh said. “That must have been quite the adventure.”

She blinked. Raised her brows at him, as if she hadn’t thought of it that way before. He shuffled a little, getting as comfortable as he could on the hard floor.

“Yes,” she said, slowly. “I suppose it was.”

Linh leaned forward.

“Tell me about it?”

So she did. Haltingly at first; but soon, she was sketching her stories in the air as she talked. tale after tale whiled away the small hours. Each one seemed to Linh more solid, more real, than a thousand boxed-up wonders.

Outside, he could hear the muffled train horn, the traffic on the highway. But above both sounds, eerie and cutting as the winter wind—

He thought he heard the howling of wolves.

Enjoy this story?

You may also like one of these!

Jester

Skies of Scarlet

The Wolf of Oboro-Teh